|

Hi!

It's THE END of 2013. It had also been a busy month for us, and a sad month for the whole world as humanity lost its champion: Nelson Mandela.

Instead of providing our own articles this time, we will instead reproduce you with 3 short blogs from the Harvard Business Review Blogs, starting with the first one by Rosabeth Moss Kanter with a tribute and call to action for the passing of Madiba Mandela.

Hence, this month's topics:

Read on... ...

To read the rest of this newsletter, pls. click here (http://www.psycheselling.com/page4.html)

We wish you a Merry Christmas, and a Great Year Ahead!

Find Your Inner Mandela: A Tribute and Call to Action

by Rosabeth Moss KanterDecember 5, 2013

Don’t just mourn Nelson Mandela. Learn to be Nelson Mandela.

He was the consummate turnaround leader. As the first democratically-elected president of post-apartheid South Africa, he took on and reversed the destructive symptoms of decline, a larger version of what goes on in any organization or community sliding downhill – suppression of information, group vs. group antagonisms, isolation and self-protection, passivity and hopelessness. He began the turnaround with messages of optimism and hope, new behaviors at the top (he even cut his own salary), and new institutions that created more communication and accountability. He created a new constitution with a participatory process that included everyone. He reached out to former enemies, visiting the widow of a particularly odious apartheid leader for tea. He ensured diversity and inclusion of all groups in his Cabinet. He brought foreign investment back to South Africa and empowered the disenfranchised black majority to take positions in those enterprises.

He knew that he was an icon and shaped a culture for others. His goal was to change behavior, not only laws. The head of what was then Daimler Chrysler South Africa, who had returned to his native South Africa after apartheid ended, motivated a hostile, unproductive black work force by engaging with them in their dream of building a Mercedes for Mandela. This was all about culture, not about financial incentives. People raised their aspirations because Mandela encouraged them.

He also understood the power of forgiveness. Despite 27 years in prison, he emerged with his sense of justice intact — but no discernible bitterness. He maintained his faith in people no matter what, that people would come right in the end, he said. His Truth and Reconciliation Commission was a masterful organizational innovation, permitting people to come forward to admit atrocities and then go forward to make a fresh investment in future improvement. He made the rare transition from revolutionary to statesman. He resisted pressure to simply switch roles from oppressed to oppressor and instead focused everyone on pride in the nation they shared and on working together for larger common goals. His wearing of the colors of the formerly all-white rugby team in South Africa’s 1995 victory over New Zealand was a dramatic healing gesture.

He didn’t cling to power. He empowered. He announced during the election that he would serve only one five-year term – a remarkable action not only in Africa, a continent riddled with corrupt leaders who refuse to cede power, but also for someone who had waited so long and given so much to reach that position. Some observers faulted him for this, because his successors were no Mandela. But he made his point – that many must serve and become leaders, and that a nation is larger than any one person.

He continued to advocate for service after he left office. He asked former U.S. President Bill Clinton to help bring a national service program like AmeriCorps to South Africa. That was the start of City Year South Africa in Johannesburg, featuring young people working in schools to improve outcomes for those who had been left behind. As a City Year trustee, I saw firsthand the positive energy Mandela unleashed.

In a mere five years in office, he couldn’t transform everything. But he could start programs and create institutions that would shift other people’s actions to a more productive path. He could serve as a role model, conveying messages through his personal actions and his words about what kind of behavior, what kind of culture, would characterize the new South Africa he envisioned.

Mandela’s legacy is larger than racial justice and more widespread than his country or continent. His legacy lies in the lessons about leadership he left for all of us. We can pay tribute by channeling him: Discouraged because things don’t break your way? Consider Mandela’s 27 years in prison. Unwilling to give up the perqs of power? Recall Mandela’s no-more-than-five-years promise. Tempted to crush the competition, eviscerate enemies, or publicly humiliate those who make mistakes? Find your inner Mandela, forgive, and move on.

As children, many of us read the powerful, disturbing novel about the evils and tragedies of apartheid in South Africa, Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton. Now the beloved country cries for the death of the leader who ended apartheid. Imagine a Mandela for the Middle East, or multiple Mandelas in the U.S. Congress. There would be more collaboration, more truth and reconciliation, more focus on common goals rather than divisiveness. That would be a gift for the world. The best way to mourn Mandela is to start a movement to transform the culture of leadership, and ourselves.

More blog posts by Rosabeth Moss Kanter The Best Way for New Leaders to Build Trust

When I took over as CEO of Intralinks, a company that provides secure web based electronic deal rooms, the company was hemorrhaging so much cash that its survival was at stake. The service was going down three times per week; we were in violation of the contract with our largest client; our chief administrative officer had just been demoted, and so on.

So, what I do on my first day? I spent more than four hours listening in to client support calls at the call center. I shared headsets with many of the team, moving from desk to desk to speak to the reps. To say they were surprised is an understatement: Many CEOs never visit the call center, and virtually none do it their first afternoon on the job.

I made this my priority partly because I wanted to know what customers were saying—but also to make an internal statement. I knew there had to be some radical changes to behaviors, expectations, and attitudes. There was no time to be subtle. I needed to show I was different, that things were going to be different, and I needed to establish trust as quickly as possible.

In leading various companies over the years, one of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned is that establishing trust is the top priority. Whether you are taking over a small department, an entire division, a company, or even a Boy Scout troop, the first thing you must get is the trust of the members of that entity. When asked, most leaders will agree to this notion, but few do anything to act on it.

This is not a common approach. Many leaders see their role as directing and giving information, rather than gathering. There is pressure to “come up with the answer” quickly or risk looking weak. Too many new leaders believe they’re expected to know the answer without input or guidance. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Doing this correctly takes time—but less than you might think. The meetings can be on one on one or small groups. The sessions can’t be rushed. In the first few weeks I’d suggest you spend up to half your time in these meetings. Take a pad and take notes. Listen intently. A simple but effective open-ended question is: “If you were put into my role tomorrow, what would be the first three things you’d do and why?” Or: “What are the three biggest barriers to our success, and what are our three biggest opportunities we have?” Really great ideas can emerge from these meetings—along with some really mediocre ones—but it’s your job to filter and prioritize them. First, gather the information.

Later on my first day at Intralinks, I began arranging meetings with individual contributors. That’s where my learning really began. Over the next few weeks I met with over 60 individual contributors. Not only did I learn a lot, but I convinced them that I cared what they thought and could be trusted with the truth.

In the middle of my first week as CEO, one of the company’s original VCs called. “So, what’s your plan?” he asked. I said I have to spend a few weeks learning. He was incredulous that I did not have a pre-baked plan. I was incredulous he thought that I should.

Over those weeks I learned how unhappy clients were with our complex bills, why service went down so often, why our pricing gave our clients headaches, that 80% of the customer calls could be eliminated with a simple fix to our service, and that clients wanted predictability of expenditures with us.

After six weeks, I had enough information to return to the management team with specific recommendations on what I thought we should do. Instead of just laying this out in an all-hands meeting, I began laying out the plan in one-on-one meetings in which I talked about how each individual’s feedback had helped guide my thinking. This created a tremendous buy in among all levels of the team.

By mid March, after only 10 weeks on the job, we rolled out the new plan. By the end of the year we’d signed 150 new long-term contracts (up from zero), revenue was up by almost 600%, our burn rate was cut by 75%, and we’d positioned ourselves to raise a $50 million round of financing a few months later in the heart of the dot.com winter.

None of this could have happened without building the trust of the team. New leaders must remember that many of the best insights on how to fix a company lie with employees further down the org chart. Creating a trusting, honest dialogue with these key personnel should be every new leader’s top priority.

More blog posts by Jim Dougherty More on: Leadership

Jim Dougherty, a veteran software CEO and entrepreneur, is a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management. Overcoming Feedback Phobia: Take the First Step

by Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman December 16, 2013

Situation 1: Asking for it

You’re sitting at your desk when an e-mail pops up from your boss that cryptically states, “Please come to my office; we need to talk.” What’s the first thing you think?

For most people it’s, “Oh no – what did I do now!” or “Good gosh, what went wrong!” Of course it is possible that your boss wants to praise you, ask your opinion on something, or just discuss an issue, but the vast majority of people will assume they’re being called in to be called on the carpet for something or another. This assumption causes many people to avoid feedback all together — and not just those whose bosses actually do criticize them a lot or those who are insecure about their performance. Generalized “feedback phobia” is widespread.

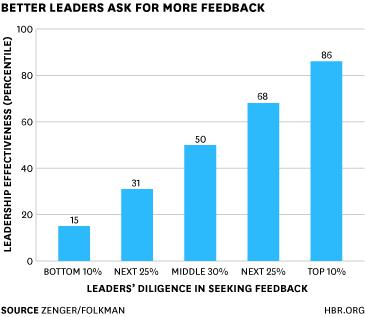

The best leaders appear to ask more people for feedback and they ask for feedback more often. Rather than being fearful of feedback, they are comfortable receiving information about their behavior from their bosses, their colleagues, and their subordinates.

Situation 2: Dishing it out

It’s 8:45 am, and you are sitting at your desk. Right on time an Outlook reminder pops up announcing “Performance discussion with Darcy Pearson, 9:00 am.” You groan out loud and then think to yourself,

Darcy’s performance has been terrible. Her attitude is bad, she has no energy, and her output is substandard.

You feel dread in your stomach. Your anxiety is high. Your blood pressure is rising. Inwardly you say,

They don’t pay me enough to do this job.

You’re thinking that no matter what you say or how you say it, the meeting will go badly. Your only thought about a possible solution is,

The sooner I start this, the sooner it will be done.

Sound familiar?

Most people can come up with several traumatic stories from their pasts in which they have given or received unconstructive, negative feedback. These terrible experiences embed themselves into our psyche and become a source of anxiety.

On the other hand, most people can also remember a time when someone gave them helpful feedback that contributed to a marked improvement in their effectiveness and influenced their success.

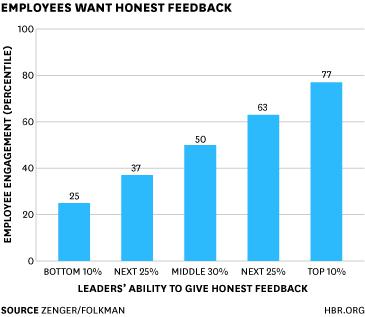

The ability to give honest feedback in a helpful way is closely aligned with employee engagement. In another recent study of 22,719 leaders, we found that those who ranked at the bottom 10% in their ability to give honest feedback to direct reports received engagement scores from their subordinates that averaged in the 25th percentile. Their subordinates disliked their jobs, their commitment was low, and they frequently thought about quitting. In contrast, those leaders who were judged better than 90% of their peers at giving honest feedback had subordinates who ranked at the 77th percentile in engagement (clearly feedback, while important, isn’t everything.)

How Good Are You at Getting and Giving Feedback? Assess Yourself

Knowing that it’s important to give and receive feedback is one thing. Knowing whether you do it well is another.

As a start, we have developed a self-assessment, which you can click on

here that can measure your desire for giving and receiving positive and negative feedback. It also measures your overall feelings of self-confidence, since that trait correlates strongly with the desire to give and receive feedback. More blog posts by Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman More on: Managing people, Managing yourself

Jack Zenger is the CEO of Zenger/Folkman, a leadership development consultancy. He is a co-author of the October 2011 HBR article “Making Yourself Indispensable,” and the book How to Be Exceptional: Drive Leadership Success by Magnifying Your Strengths (McGraw-Hill, 2012).

Joseph Folkman is the president of Zenger/Folkman, a leadership development consultancy. He is a co-author of the October 2011 HBR article " Making Yourself Indispensable," and the forthcoming book How to Be Exceptional: Drive Leadership Success by Magnifying Your Strengths (McGraw-Hill, 2012).

About Directions Management Consulting

Whether you like it or not:

Yet, getting results through people is just so imperative in today's interdependent work environment.

So if this the case, then how do we

help you to

Get Better Results through

People?

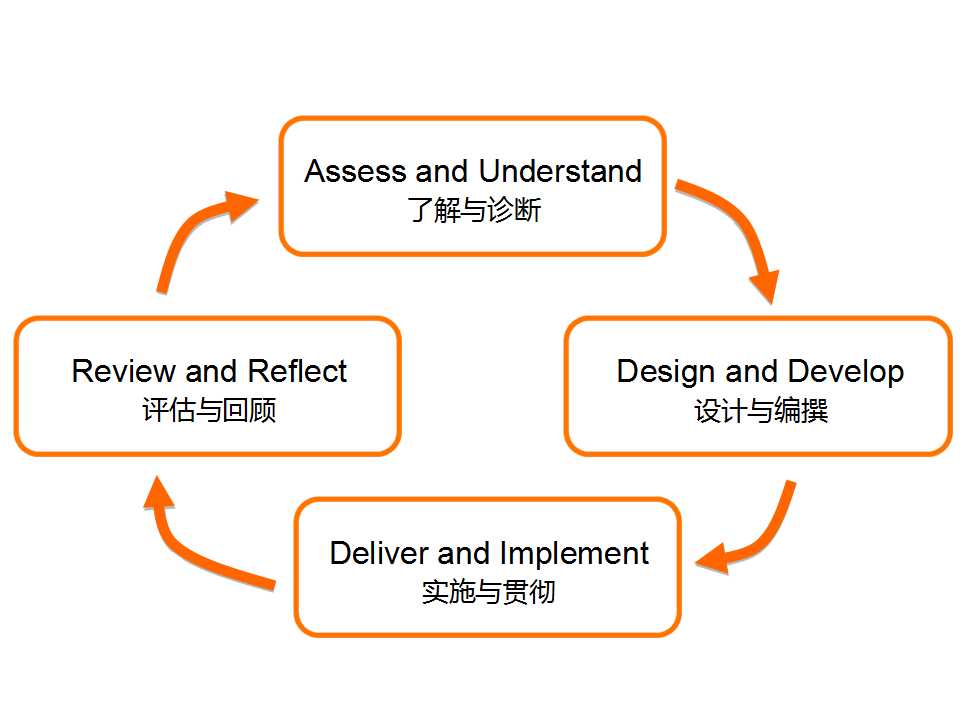

First, we assess the current

situation on what are the various

areas that need to be changed or

addressed. We assess the behavioural

styles of individuals and teams. We

seek to understand the work

relationships and interactivity

between people and departments,

between bosses and subordinates, as

well as with customers and

suppliers. We seek to understand

what is the current situation, and

what goals you want to achieve.

The tools we use include

Belbin

360,

Global Mindset

Inventory,

Cultural

Orientations Approach,

DISC,

MBTI,

5D

etc. amongst others. You can contact our General Manager, Mr. Gregory Whitehorn at greg@directions-consulting.com or through our office number +86-21-6219 0021 if you'd like to find out how else we can help you Get Results through People.

|